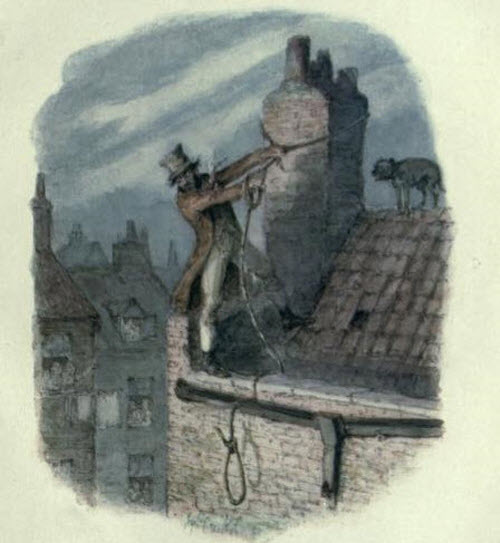

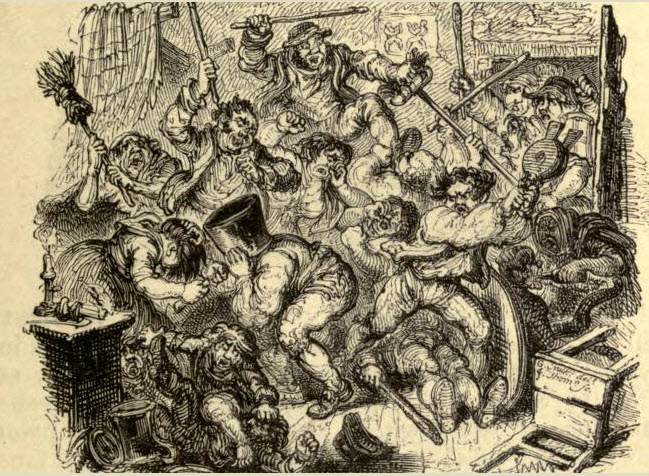

cottages, Elizabethan mansion-houses, and other old English scenes, he depicts with evident enthusiasm.

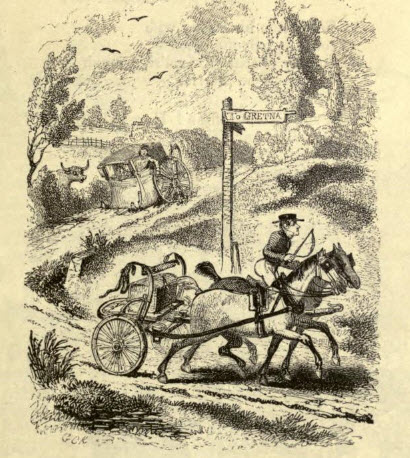

Famous books in their day were Cruikshank's 'John Gilpin' and ' Epping Hunt ;' for though our artist does not draw horses very scientifically, -- to use a phrase of the atelier^ -- he feels them very keenly; and his queer animals, after one is used to them, answer quite as well as better. Neither is he very happy in trees, and such rustical produce; or rather, we should say, he is very original, his trees being decidedly of his own make and composition, not imitated from any master. Here is a notable instance.

Trees or horse-flesh, which is the worst? It is impossible to say which is the most

villainous.

But what then? Suppose yonder horned animal near the postchaise has not a very bovine look, it matters not the least. Can a man be supposed to imitate everything ? We know what the noblest study of mankind is, and to this Mr Cruikshank has confined himself. Look at that postillion; the people in the