Discover the fascinating world of George Cruikshank, the renowned artist, caricaturist, and social commentator of the Victorian era. Our website offers a treasure trove of information about Cruikshank's life and art, including his iconic illustrations for Charles Dickens' novels, political satires, and social critiques. Immerse yourself in the vivid and often provocative imagery that made Cruikshank a household name in his time and a lasting influence on the world of illustration. With in-depth articles, stunning visuals, and engaging insights, our website is the ultimate resource for anyone interested in the life and work of this visionary artist. Start your journey into the world of George Cruikshank today!

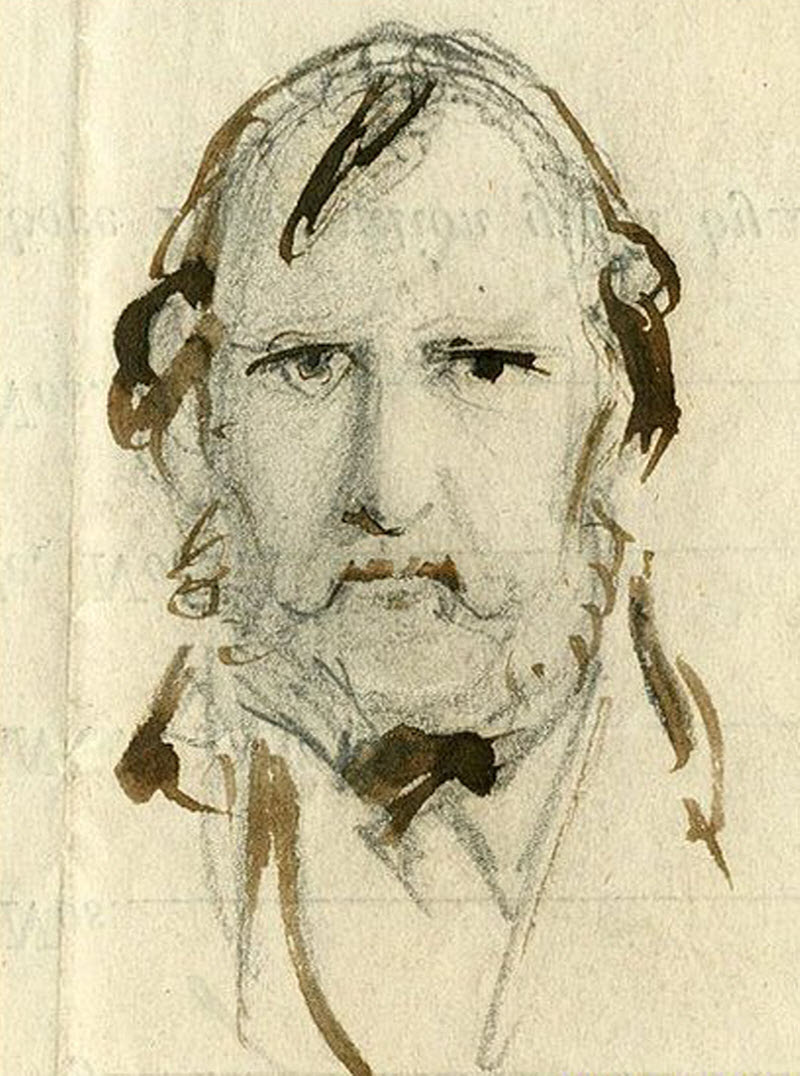

Who was George Cruikshank?

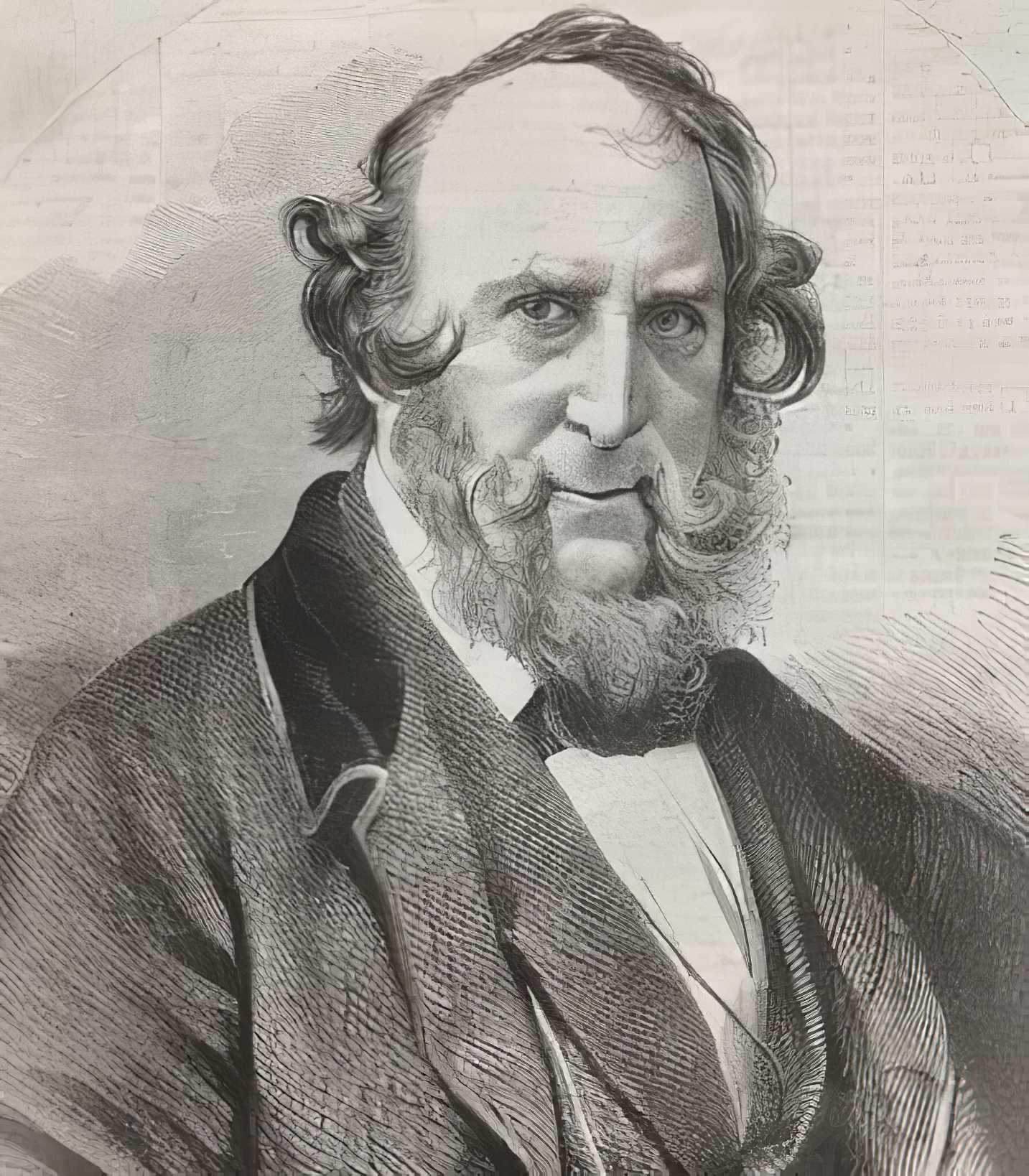

George Cruikshank was the foremost British illustrator and caricaturist of the 1800s. During his career, Cruikshank produced well over 10,000 drawings and etchings ranging from book illustrations to political caricatures and social satire. He illustrated over 860 books plus countless periodicals and magazines. His illustrations for the novels of Charles Dickens and many others, brought him great fame during his lifetime. His masterful technique has had a lasting impactr on the art of caricature and book illustration, and even laid the foundation of the modern graphic novel.

George Cruikshank was the son of Isaac Cruikshank, one of the greatest cartoonists of the time. Cruikshank learned his trade by working as an assistant and pupil of his father. His older brother, Robert Cruikshank, also followed in their father's footsteps and eventually became an illustrator and caricaturist as well.

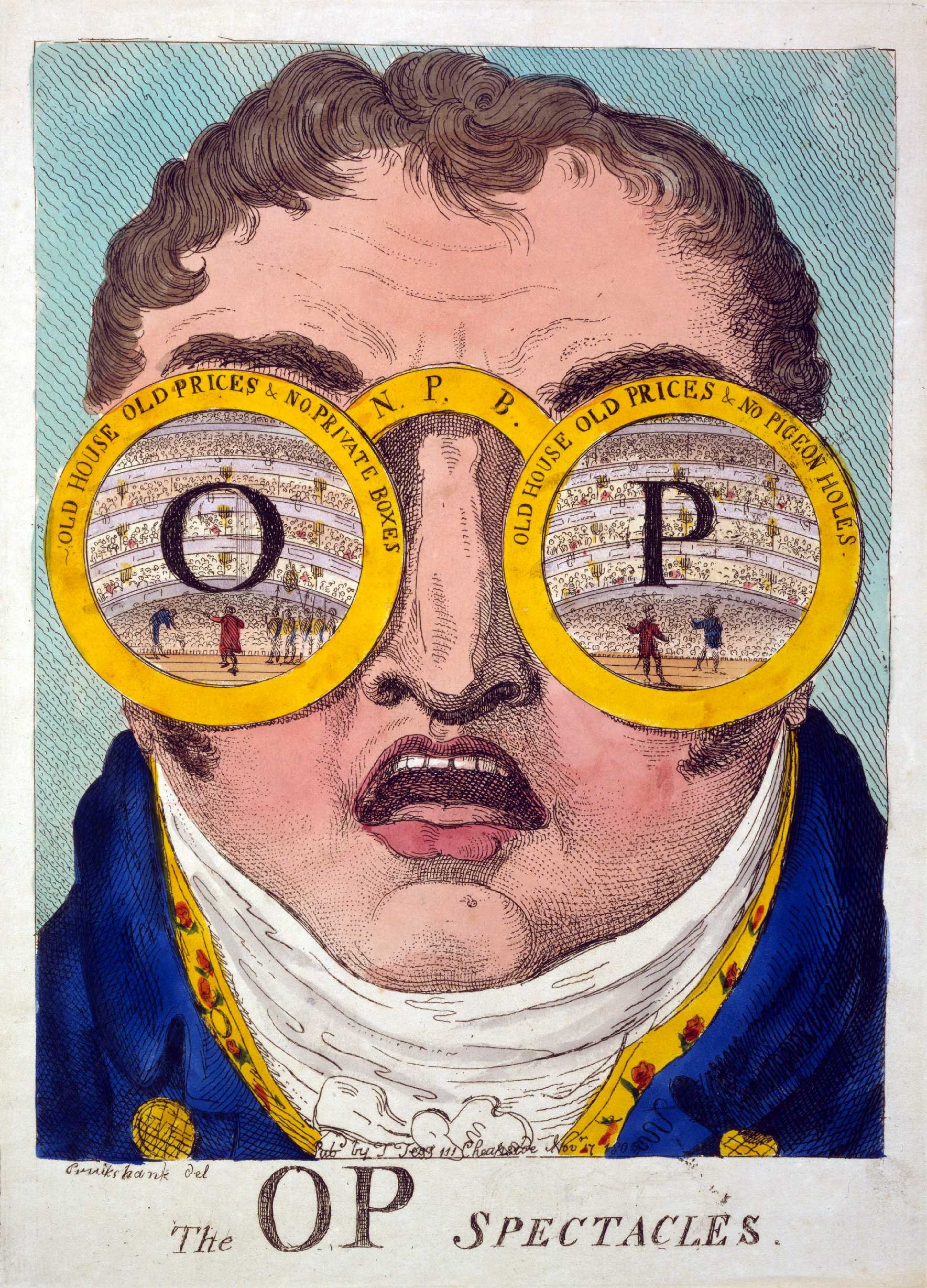

Cruikshank's early work consisted mainly of caricatures and political satire. His favorite targets were the Royal family and leading politicians of the time. His satirical attacks on the Royal Family were so savage, that it is said that King George paid him a large sum not to caricature him. Cruikshank also gained inspiration from political and social events of the time. He drew cartoons satirizing British foreign policy, particularly imperialist wars with China and its rivalry with France. His drawings which satirized contemporary society were especially well received, and he was favorably compared to the great Hogarth, as well as to James Gillray, whom Cruikshank acknowledged as an early influence.

His satirical genius first found expression in “The Scourge,” a periodical published between 1811-16. At this time his caricatures were in the style of Gillray, but about 1819 he began to illustrate books and developed a style of his own. Among his caricatures those of Napoleon, the impostures of Joanna Southcott, the corn-laws, the domestic infelicities of the regent and his wife, etc., are noted.

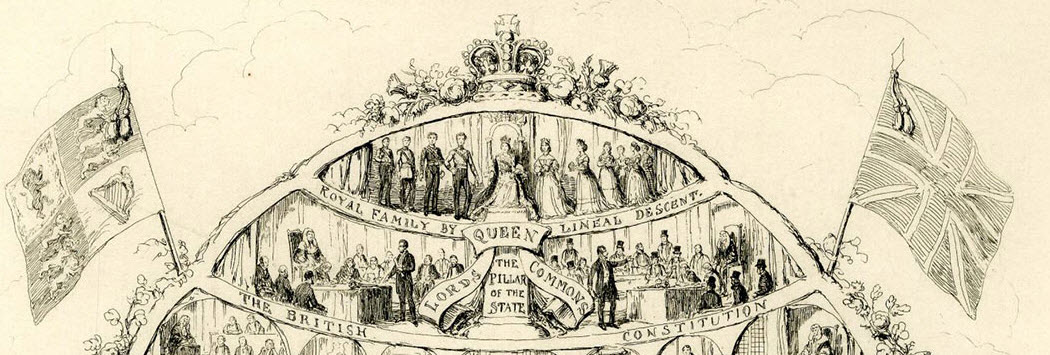

A committed British patriot, to the point of over zealousness, Cruikshank also devoted his considerable talent to pro-British propaganda, including developing the character of John Bull, the personification of the British people. He also drew the British Bee Hive, an idealized illustration of British society.

In 1827 William Hone issued a collection of Cruikshank's caricatures in connection with the latter scandal, which he called Facetiae and Miscellanies. Some of his best illustrations were for Scott and for a translation of German fairy tales. In 1823 he issued his designs for Chamisso's Peter Schlemihl.

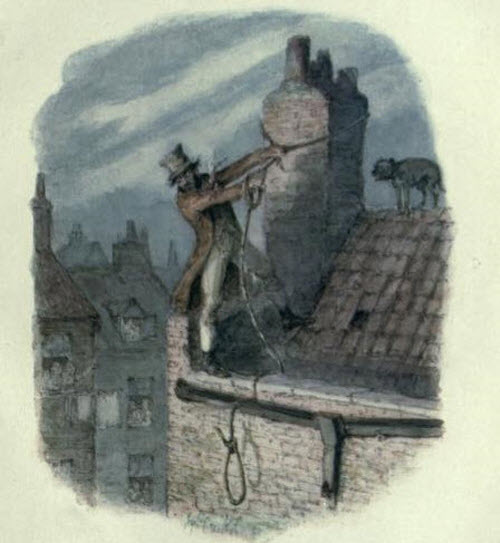

George Cruikshank later expanded his artistic horizons and focused more on book illustrations. His illustrations adorned the works of great authors such as Charles Dickens, Sir Walter Scott and William Ainsworth and he gained international fame as a book illustrator. His collaboration with Charles Dickens led to a friendship between the two men, but they had a very public falling out when Cruikshank took credit for "Oliver Twist," claiming that he had suggested the plot to Dickens. Cruikshank later had a similar controversy with the author William Ainsworth, claiming that he was the creator of one of his books as well. Despite these controversies, Cruikshank's career flourished and his book illustrations brought him international fame.

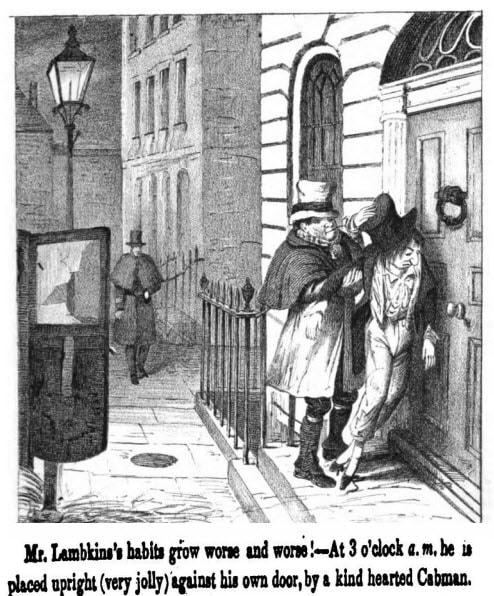

Later in life, Cruikshank devoted himself to social causes. Although he had been a heavy drinker and smoker as a younger man, Cruikshank now used his satiric talents to attack these vices. He devoted himself with great zeal to the temperance movement, drawing many cartoons and illustrations in favour of abstinence and exposing the horrors of alcohol abuse. “The Bottle” (eight illustrations, 1847) and “The Drunkard's Children” (eight plates, 1848) were Cruikshank's first products of his satirical crusade against drunkenness. In recognition of his efforts, Cruikshank was elected the President of the National Temperance League, a British organization that advocated for alcohol prohibition.

Later in life, Cruikshank devoted himself to social causes. Although he had been a heavy drinker and smoker as a younger man, Cruikshank now used his satiric talents to attack these vices. He devoted himself with great zeal to the temperance movement, drawing many cartoons and illustrations in favour of abstinence and exposing the horrors of alcohol abuse. “The Bottle” (eight illustrations, 1847) and “The Drunkard's Children” (eight plates, 1848) were Cruikshank's first products of his satirical crusade against drunkenness. In recognition of his efforts, Cruikshank was elected the President of the National Temperance League, a British organization that advocated for alcohol prohibition.

To some extent, Cruikshank's sermonizing appears hypocritical given his personal choices. Cruikshank was married twice. His first marriage, to Mary Ann Walker (1807 to 1849) ended with Mary's death. Two years later, Cruikshank married Eliza Widdison. They remained married until his death and by all appearances the couple lived a content and traditional Victorian marriage. Cruikshank did not have any children by either of his wives, but upon his death it was discovered that George Cruikshank had actually fathered eleven children! with his mistress, a former servant, whom he had installed in a house just a few doors down from where he lived with his wife. The affair only came to light due to provisions in his will, which left part of his estate to his mistress and their children. How remarkable that he could not only keep his relationship secret for all of these years, but somehow ignore or at least fail to publicly acknowledge his enormous brood of illegitimate children living just down the street from him. One has to wonder whether he felt any stress or discomfort at the double life he was leading, and whether he ever feared discovery. If he did, it was not reflected in Cruikshanks's illustrations which continued to display great effortlessness and naturalness.

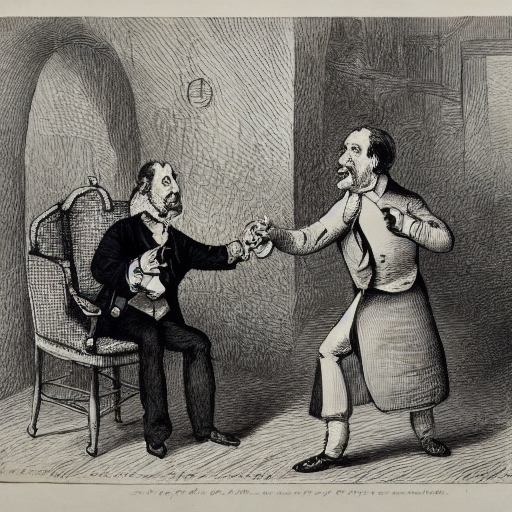

Above is a fanciful Illustration by George Cruikshank of the Artist Among His Characters. They appear to have a life of their own, and one of them is sketching the artist, as he too is apparently a figment of the imagination.

Towards the end of his life, George Cruikshank suffered a stroke which left him partially paralyzed. The stroke affected his health and the quality of his work also suffered. His health continued to deteriorate, and he died on February 1, 1878 at the age of 85. Cruikshank was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral. The daily newspaper Punch Magazine, apparently ignoring his not-so-pure life of heavy drinking and marital infidelity, wrote in his obituary: "There will never be a man so pure, simple, fair, yet ruthless in whip and customs of our times. His nature had the innocence of a boy in its transparency."